From promenade to pulled down: how a vision was lost

Any student of Ballarat’s history, indeed any proud Ballaratian, would know Sturt Street was not the original shopping strip of the city.

While Sturt was much older as the gateway to the Pyrenees, the prosaically-named Main Road rose to prominence following the discovery of gold. Washed out in winter and dusty in summer, it was plank-lined to make it passable. Ballarat grew so quickly, without any planning of a discernible nature – miners took their claims and simply wore paths which became ersatz streets – that overcrowding and poor sanitation led to outbreaks of disease and discontent.

READ MORE:

Enter the splendidly-named William Swan Urquhart.

Urquhart was appointed assistant surveyor to Her Majesty’s Colonial Government by Robert Hoddle, the planner of Melbourne. Regarded as capable, well-educated and reliable, Urquhart made his first visit to what would become Ballarat in 1847, surveying the Lal Lal creek, the ranges around Warrenheip, Buninyong and Black Hill, and the Dividing Range between the Werribee and Yarrowee rivers.

Returning in December 1851, he laid out the ‘Plan of Ballaarat Township reserve’, moving his vision of a European city of culture from the ‘higgledy-piggledy’ layout of Ballarat East to the basalt plateau of the west.

Following the template of the time, based on the rebuilding of London, Urquhart described a grid centred around the existing three-chain (66 yards, 60 metres) main route, which he named Sturt Street after the superintendent of the District Police Force (covering Melbourne and the County of Bourke), the also splendidly-named Evelyn Pitfield Shirley Sturt.

But time is relentless, and Ballarat suffered more than many cities in the downturn of the 1890s and in its losses during World War One. While its population remained steady, income for the city declined. The vivacity and intention of the boom buildings needed money, and by 1929 it was in short supply.

The roads were constructed so wide to accommodate the turning of bullock teams and drays laden with wool going one way from the western districts and goods returning – including the press made to publish The Courier.

A remnant of the old Ballarat is the curve of the already-established Camp Street, home of the police and government camps overlooking the diggings, upsetting the layout.

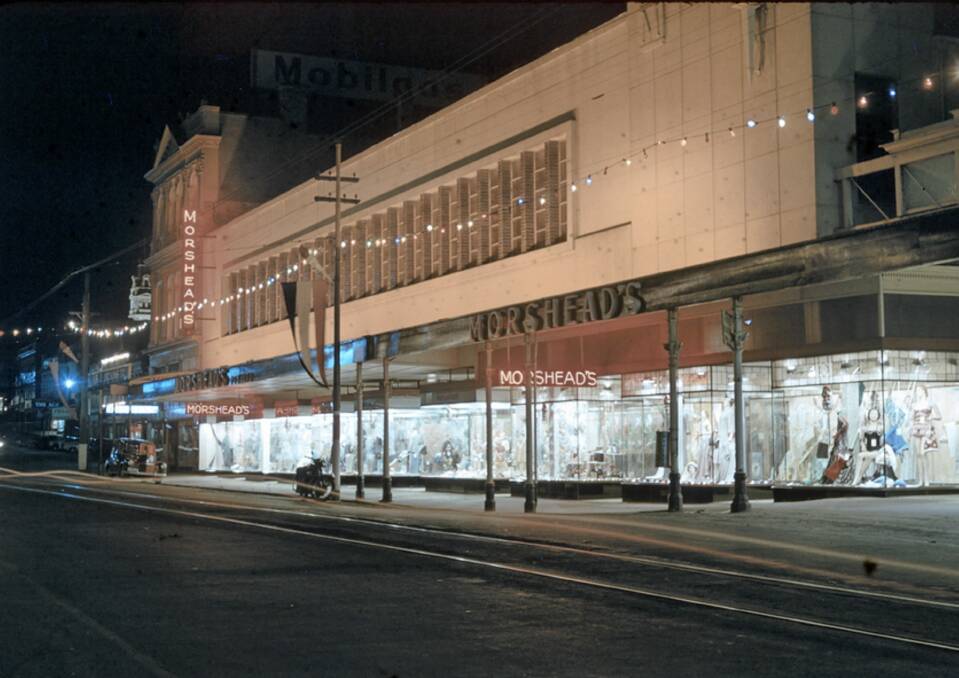

As the revenue from the shares in gold companies began to flow back to local investors. Ballarat soon moved from a settlement of canvas, daub and weatherboard to a grand city of brick, basalt and marble.

In 1871 the English writer Anthony Trollope regarded it as ‘the metropolis of the Australian goldfields’; the American Mark Twain wrote of his 1895 visit, ‘it has every essential of an advanced and enlightened big city’.

The locals, grown rich on gold, were not stinting in either building palaces to commerce or funding philanthropic institutions.

The Benevolent Asylum, Orphanage, Art Gallery, Ballarat Hospital and a host of others rose, often designed by the best architects available and paid for by benefactors who sported top hats and gold watchchains wrought from nuggets they had dug with hands so weatherbeaten they could not hide their owners’ former professions.

But time is relentless, and Ballarat suffered more than many cities in the downturn of the 1890s and in its losses during World War One. While its population remained steady, income for the city declined. The vivacity and intention of the boom buildings needed money, and by 1929 it was in short supply.

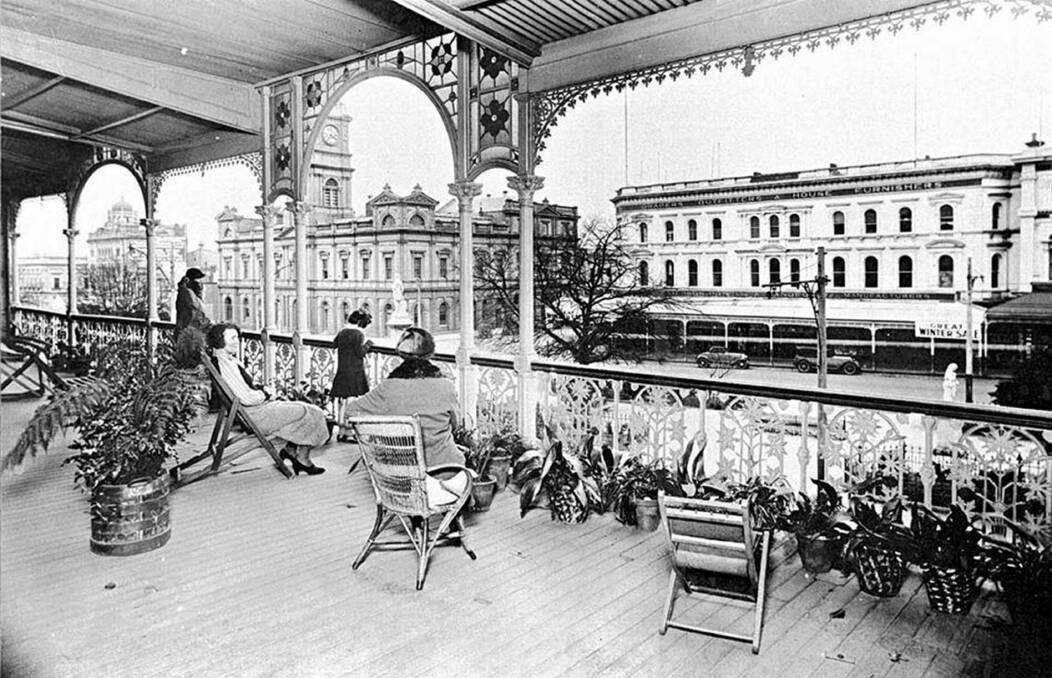

The big buildings of the city came under threat either through renovation or demolition. The Ballarat East Town Hall fell. The Benevolent Asylum. The Ballarat Orphanage. The Alfred Hall. The magnificent Grenville College in Holmes Street, suffering the undignified fate of housing a tomato sauce factory at its end, went in the 1950s and remains a blank site to this day. Cohen’s Grand Hotel in Lydiard Street, the stunning Lester’s Hotel and Criterion House on the corner of Doveton Street. All gone.

As the revenue from the shares in gold companies began to flow back to local investors. Ballarat soon moved from a settlement of canvas, daub and weatherboard to a grand city of brick, basalt and marble.

It was combined with the zeitgeist of modernisation run by the councils of the period, who ordered the tearing down of the verandahs of the city on the spurious grounds that increased motor traffic might strike a cast iron post and bring down the structure.

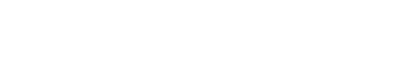

What it really struck was a major blow to the Victorian ideal of promenading, of wandering up and down Sturt Street as a pastime. The verandahs had provided shelter from Ballarat’s frequent inclement weather, hot and cold, as well as venues for social interaction, such as the balcony of Lester’s Hotel.

In the end, the trams went; the magnificent Nicholl Drapers building was remodelled and the London and Mutual Bank building was demolished. In 1963 Ballarat City Council proposed to tear up the Sturt Street Gardens for an underground carpark.

The big buildings of the city came under threat either through renovation or demolition. The Ballarat East Town Hall fell. The Benevolent Asylum. The Ballarat Orphanage. The Alfred Hall. The magnificent Grenville College in Holmes Street, suffering the undignified fate of housing a tomato sauce factory at its end, went in the 1950s and remains a blank site to this day. Cohen’s Grand Hotel in Lydiard Street, the stunning Lester’s Hotel and Criterion House on the corner of Doveton Street. All gone.

Norwich Plaza was the beginning of the era of the mall mentality, but also of the idea of buildings being replaceable. Urquhart’s vision of a European city the equal of Edinburgh or Manchester, of Athens or Barcelona, was lost to the motor vehicle and the mundane.

My thanks to Anne Beggs-Sunter, Dot Wickham and Wendy Jacobs for assistance with this article.