The day 44 people were killed in a Ballarat train crash

A TERRIBLE TRAGEDY

The roar of the crash was indescribable. The screams of the injured and dying mixed with shattering glass, splintering timber and torn metal. Gas and steam hissed through the air, followed by sound of flames igniting. Yellow flame flickered through the night, lighting a nightmarish scene.

At 11 minutes to 11pm on April 20, 1908, two Melbourne-bound trains, one coming from Ballarat, the other from Bendigo, collided at the new Sunshine railway station. The combined passengers of the services numbered near 1100.

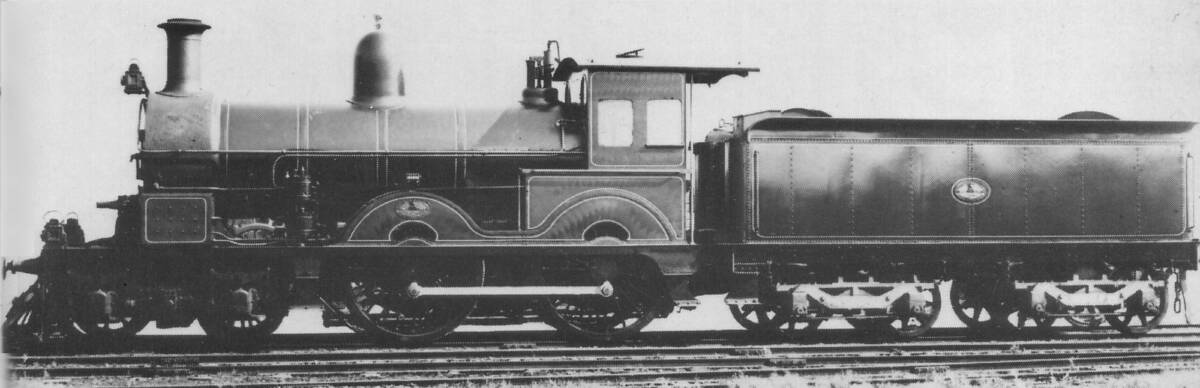

The Bendigo train’s two AA engines, built at the Phoenix foundry in Ballarat, and their coal tenders ploughed into the rear of the train standing at the platform, telescoping four carriages and the guard’s van into a pile of bloodied demolition, and causing them to catch fire. The weight of just one engine and tender was reported in The Argus as 90 tons.

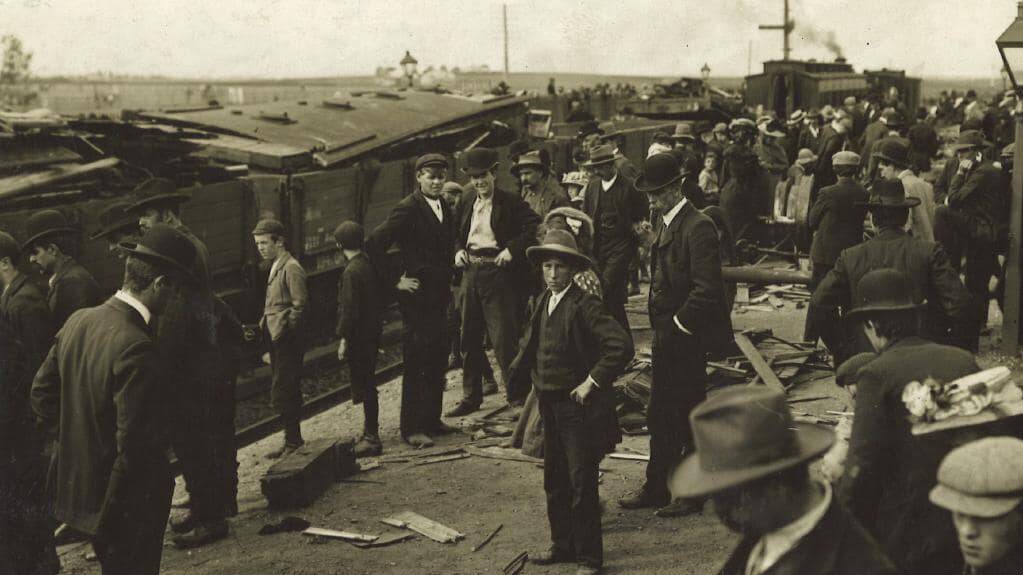

Passengers who had already alighted on the platform ran to assist, while others shielded children’s eyes from the horrific sight. Those who survived ran or crawled from the wreck, panicked. Women and men fainted as they watched.

The station, built to transport the workers at H.V. McKay’s nearby Sunshine Harvester factory, was so new it had no stretchers, firefighting equipment or even axes. The only tool available at first was a rabbiter’s axe taken from a nearby farm. Its aged handle soon shattered. Local firefighters extinguished the blaze and teams of locals and passengers set to work pulling apart the shattered carriages.

The carnage was terrible. Both trains were overcrowded with passengers returning from the Easter holidays – newlyweds, sporting teams, excursioners – and extra carriages had been added to accommodate the numbers. Reports of the time had many standing in the passageways and jamming themselves into compartments.

It was an awful smash. You cannot describe it. All I can say is that it gave me the impression of something hard being shoved into some soft substance, and the latter being tossed into the air. There were heartrending screams from the injured passengers. I rushed across, and helped some of the ladies out. I was nearly knocked down by panic-stricken men who flung themselves out of the wrecked carriages. Having had nothing to eat for about ten hours, the scenes of suffering made me feel quite faint.

- John Richards, eyewitness, in The Argus, 1908

Forty-four people were killed. Over 400 were injured. The newspapers of the time were graphic in their reportage of the tragedy, giving detailed descriptions of injuries suffered and discoveries of the dead.

HOW DID IT HAPPEN?

Heads were crushed in and flattened; necks were entirely, and almost entirely, severed; and livid, blackened, open-mouthed corpses stared grimly towards the heavens, their battered features still showing the contortions of horror into which they had been twisted; or the tortures of suffering experienced at the approach of death's horrifying spectre. Amongst the rows of death there was the body of a woman, with both her legs from the ankles to the thighs tightly bound in splints and bandages. She had received relief such as could be afforded, but she was dead.

- The Age, April 22, 1908

Both trains were running late because of the numbers of passengers. The Ballarat service had arrived at 10.47pm, over 40 minutes after it was due; it had been forced to make two stops at each station because of its extended length.

The Bendigo train was running 20 minutes behind. Engine driver Leonard ‘Hellfire Jack’ Milburn had been told to drive his engine at ‘express’ speed and stop only at stations where passengers desired to alight.

The extra carriages meant the Ballarat train had to disembark the forward carriages then move further along the platform to align the rear. It was at this point the Bendigo train, sparks streaming from its wheels, smoke and steam pluming from its smokestack as Milburn attempted to stop it by reversing the engine, cannoned into the guard’s van.

Milburn was an experienced and respected driver, no careless man. His nickname referred to his capability as an express engineman, not a reckless disposition. He brought the Bendigo service into the station via an ‘all clear’ signal at Sydenham (now Watergardens). The train was now seven miles (11km) from Sunshine.

At this point the obscure and difficult topic of rail signalling enters. As simply as can be explained, railway station signalmen (no signalwomen then) control ‘blocks’ of rail track between signal boxes. By sending bell messages, they alert each other as to where a train is at any given point.These alerts are then transferred to the green and red semaphore signals and lights on the lines to be seen by drivers.

Errors were made in signalling that allowed the Bendigo train to head towards Sunshine Station. It passed two signals set to danger, one at 900 yards from the station and another at; at this point driver Milburn threw the Westinghouse brake on his service. It failed, he said, and he realised an impending disaster loomed.

Milburn and his other drivers and firemen said their train was travelling at 23 miles an hour (40kmh). Other witnesses, including rail workers, put it closer to 40mph (65kmh), although they refused to testify to that at the inquest.

I saw half a dozen dead bodies. Legs and arms that had been cut off were lying around, and in the wrecked carriages some people were found with the life crushed out of them, hanging by their chins from the hat rack, against which they had been jammed when the Bendigo engine ploughed its way into the train.

- Mr G. Symonds, Ballarat

At any rate, Milburn could do nothing but stay in his engine, trying to slow it by hurling the engine into reverse and opening the steam cocks. It was useless. His engine rode up onto the bogey of the guard’s van, the Ballarat guard John Fraser having got clear just before, waving frantically and helplessly his kerosene lamp, signalling for the Ballarat driver to pull clear of the platform.

“Just before the impact occurred,” he said, “I made a dash for the picket fence. The rest was just awful.”

HORROR AND HEROISM

The inadequacy of the safety and rescue equipment was compounded by an almost-preternaturally cruel attitude pursued by some in the the Victorian Railway Department.

After a delay of hours, the forward part of the Ballarat train, carrying injured and shocked passengers, was taken towards Melbourne. Some of the female passengers had torn their dresses to make bandages for themselves and others. At North Melbourne the train was halted while rail officials demanded tickets of the passengers as if nothing had happened.

The action was later described by the Railway’s Chief Commissioner Thomas Tait as ‘gross stupidity’. The 13-stone, cigar-chomping, 3000-a-year Canadian Tait was determined to deal with the tragedy in the same manner he had reformed the railway – by doing it his way.

Relief trains carrying rescue equipment, trained staff and ambulance wagons to transport the injured were stopped at West Footscray, taking 35 minutes to reach the station from Melbourne, just four-and-a-half miles(7km) away. Meanwhile at the site of the disaster, in the black of night, the dead, dying and injured were laid out on both sides of the Sunshine platform, in the waiting rooms and the paddock beyond. People rushing about the station tripped on the dead.

Tait spoke to the press, visited the injured in hospital, suspended the Bendigo train crew and the Sunshine stationmaster. He gave a interview on the cause of the crash remarkable for its transparency at the time.

At 2.30 am the last of the dead were discovered and removed. A train brought their bodies to Spencer Street Station, which was serving as a temporary morgue. The solemn and chilling site of fresh coffins and caskets, some unvarnished, being delivered drove home the enormity of the tragedy. The first body transferred to the waiting room, long since demolished, was that of a 16-year-old girl. Silence descended, men removed their hats.

One man's corpse, with the head completely torn off, lay close by the mangled body of a mother with her dead baby clasped in her arms. The body of another man was hanging up between two of the carriages in a position where for a long time the workers could do nothing to extricate it. It was with the greatest difficulty that many of the bodies could be extricated at all, as they were impaled on the ends of sharp splintered woodwork.

- The Age, April 21, 1908

A young boy wandered with his mother, searching for his father. The newspaper reported the awful scene:

“There was a look of determination on his little, pale face, which said in so many words, "Bear up, mother; I will help you to find him." That little lad had, with the approaching dawn, taken the load which seem to have slipped on to his young shoulders. It was the last and most pathetic incident of a long night.”

The coroner Dr Cole dealt with the death certificates expeditiously, to alleviate the grief of the families. In the end 10 bodies which remained unidentified were removed to the morgue on the banks of the Yarra. The premier Sir Thomas Bent ordered an inquiry.

INQUEST, CHARGE AND ACQUITTAL

The coroner’s inquest took two months. Eighty-five witnesses were called, and 31 days were taken with the giving of evidence. The jurors recommended charges of manslaughter against the two Bendigo drivers Leonard Milburn and Gilbert Dolman, and the stationmaster Frederick Kendall. Kendall’s charge was dropped later, and while Milburn and Dolman faced the Supreme Court, they were acquitted.

The accident cost Victorian Railways £125,000 in liability payments and another £50,000 in damages to rolling stock and track. It also paid for the inquest. At a rough calculation £175,000 is worth $25 million today, at 4 per cent inflation.

Not that it made any difference to Hellfire Jack Milburn. Reduced to a quivering wreck in the days after the tragedy, the 56-year-old, a 32-year veteran of the railways of Victoria, never drove a train again.

The Sunshine Railway tragedy was the first story by The Age to feature a photograph.