Manning the guns: A Ballarat digger recalls fighting in New Guinea

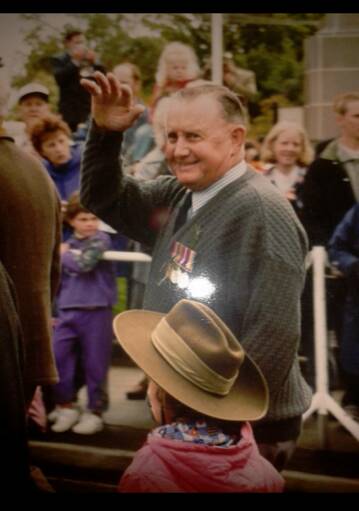

Born on the corner of Ripon and Latrobe streets in September 1924, Mark Henry Carroll is a true Ballarat native.

Aside from his time fighting the Japanese Imperial Army during World War Two, the former plumber has lived in and loved his hometown all his life, starting with his education at St Aloysius Primary School in Ripon Street and St Patrick’s Primary School, or ‘Drummo’, where he says the Christian Brothers taught him the value of discipline.

“They were tough there. They didn’t muck around bringing the strap out,” Mr Carroll, now 93, says.

His father is an asphalter, but supplemented the family income in a more traditional vein.

“In his spare time – with a lot of other fellows – he used to go down to the Yarrowee Creek near the Sunnyside Woollen Mills, and they had little shafts they used to sink to get gold,” says Mr Carroll.

And did they do any good?

“Well… they didn't make a million dollars... they made a little bit every now and again. Enough to keep them going. A few people did that during the Depression.”

On the Christian Brothers in Drummond St: They were tough there. They didn’t muck around bringing the strap out

- Mark Carroll

Mark Carroll’s father dies when he is 12, in 1936, leaving a family of 10 children. By the time he is 17, the Second World War is at a crucial point. Singapore has fallen disastrously; the Battle of Midway has inflicted severe losses on the Japanese. Prime Minister John Curtin has diverted Australian troops bound for Burma back to defend the country; Darwin has been bombed.

All noble reasons to enlist, but Mark Carroll has a more prosaic decision for donning the khaki.

“All my friends, at my age or a littler bit older, they all got called up and I was left and I thought, ‘I want to be with them.’

“So I went down to the Drill Hall, near where Big W is now, and I joined up there, no questions asked!

“Mum, she wasn’t over-keen on it,” Mr Carroll says in what may be an understatement of some proportion.

Called to Camp Royal Park in Melbourne, he’s given a uniform and shipped to Puckapunyal for three months’ training, before being moved onto the Greta army training camp in the Hunter Valley of NSW. Following this, Mr Carroll goes to the newly established Jungle Training Centre at Canungra in Queensland for the infamously tough six-week jungle warfare course.

“But when the first six weeks finished, they said, ‘Well, we got nowhere to send you just yet. You’ve got to do another six weeks. ‘But it come right on Christmastime, and they said, ‘Well, you’ve got to stop here for another six weeks.’

Our task for 1942 is stern ... The position Australia faces internally far exceeds in potential and sweeping dangers anything that confronted us in 1914-1918. The year 1942 will impose supreme tests. These range from resistance to invasion to deprivation of more and more amenities...

- PM John Curtin, 'The Task Ahead'

“So we done 18 weeks’ jungle warfare training, climbing ropes and all that sort of business… up those big high mountains with full pack… 30-mile route march, not every day but quite often. We were fit, I’ll tell you.”

The troops are given IQ tests with the idea of determining suitable roles for them within the AIF, and Mark Carroll finds himself at gunnery school nearby Canungra, training as an artilleryman with the 4th Australian Field regiment on the 100lb, 5.5 inch medium gun howitzers issued after the Great War.

“Well they were very big guns, but when we were due to go, we went with 25lb guns - still a big gun. With a super-charge (an extra load of explosive) in, you could get 7.5 miles with it, and pretty accurate.”

Mark Carroll embarks for the war in New Guinea on an old, stinking cattle boat called the Vito Oslo. Sailing from Townsville, he realises there are no beds, just constantly, ever-swinging hammocks…

“Just about eight hours out into the sea, it was pretty rough...we were all sick. Real sick, I'll tell you. This sergeant bloke was coming around having a look at us and he said to me, ‘What's wrong with you?’

“I said, ‘I think I'm seasick.’ I won’t tell you the rest of what he said, but it wasn’t complimentary. We went straight to Lae; it was about three days I think.”

The ship is too large to come alongside the jetty at Lae, so the men go over the side fully-laden and climb down cargo nets to waiting barges. Later their guns are brought ashore and towed inland; inland as far as the conditions, wet or dry, would allow. After that, the Australian soldiers relied upon the skills and strength of the indigenous New Guineans, the famous ‘Fuzzy-Wuzzy Angels’.

Mark Carroll remembers the native carriers as strong, compassionate men, quiet and dedicated.

“Oh those Fuzzy Wuzzys were great. When we went inland with the guns, the only way we could get our shells in there was with them carrying a 25-pounder (11kg shell) on each shoulder - so 50lb of shell they carried.

Oh those Fuzzy Wuzzys were great. When we went inland with the guns, the only way we could get our shells in there was with them carrying a 25-pounder (11kg shell) on each shoulder - so 50lb of shell they carried.

- Mark Carroll

The New Guinean carriers also help move the field guns into the hills, dragging and carrying the 1.6 tonne pieces into position alongside the gun crews. When the mud becomes impassable, trees are cut to make improvised roads.

The field regiments take up positions to the rear of the fighting and await directions from commandos and other infantry on the front line, telling them where to direct their shelling. Accuracy was important to avoid firing upon their own troops, which happened occasionally.

The men on the gun crew share the load of the work: laying (aiming) the weapon, loading and firing, clearing blockages in the breech, defending their position. The gunners are armed with .303 SMLE rifles and a Bren gun. Each round they fire is a shell rammed home with a rod, followed by the charge – sometimes two, called a super charge.

They are expected to defend the gun to the death and not let it ever fall into enemy hands.

“Every now and again the commandos or the infantry would give us an invitation to go up and see the damage that we’d done,” says Mr Carroll.

“And – I mean – you wouldn’t believe it. What we did see… We used high explosive and with the eight guns (in a battery), sometimes we’d get 100 rounds of gunfire (into a target). We called it a ‘ladder’. One lot of shells would drop short, one lot would go further on, and then they’d start creeping in. And we’d hit the target.”

The roar of the 25-pounder temporarily deafens the crews, who aren’t issued hearing protection. To this day Mark Carroll suffers from the roar of the supercharge rounds, and wears hearing aids.

So I thought, ‘I’ll fix him without shooting.’ I had my big army boots on, with steel caps, and I walked up behind him and I went BANG! Right in the nuts.

- Mark Carroll

His hearing loss didn’t deter him from capturing one of the enemy though – in a most unorthodox manner.

Conducting guard duty at an encampment, he spots a Japanese scout peering through the barbed wire. Reporting it to his camp sergeant, Carroll is told, ‘You seen him – you go get him’.

Carrying the Bren gun, he works his way up behind the unknowing spy, who is standing with his legs spread, observing.

Mark Carroll takes up the tale.

“He was standing there with his legs wide open looking, and I had the Bren gun, and I thought they want all the information from these blokes. So I thought, ‘I’ll fix him without shooting.’ I had my big army boots on, with steel caps, and I walked up behind him and I went BANG! Right in the nuts.

“And he collapsed.And I took him back to the sergeant and said, ‘You sent me out to get him. Here he is.’

“Later on I saw him being taken away. He was still doubled over.”

Following the war, Mark Carroll married, and became a plumber with his brother. His three sons followed him into the trade, and his business ran for 58 years.

The house he built his beloved wife (secretly, with the money he saved from his army pay) for a surprise home after they returned from their honeymoon, is still standing in Park Street.

Speaking about the war, Mark Carroll says while it’s easy to recall amusing anecdotes, “overall it was a pretty terrible thing. Not much to laugh about.”