Build it, and they will come.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

And they did.

A century on, they come still, in their millions, in tourist buses and hire cars, to experience the coastal drive regarded among the world’s best.

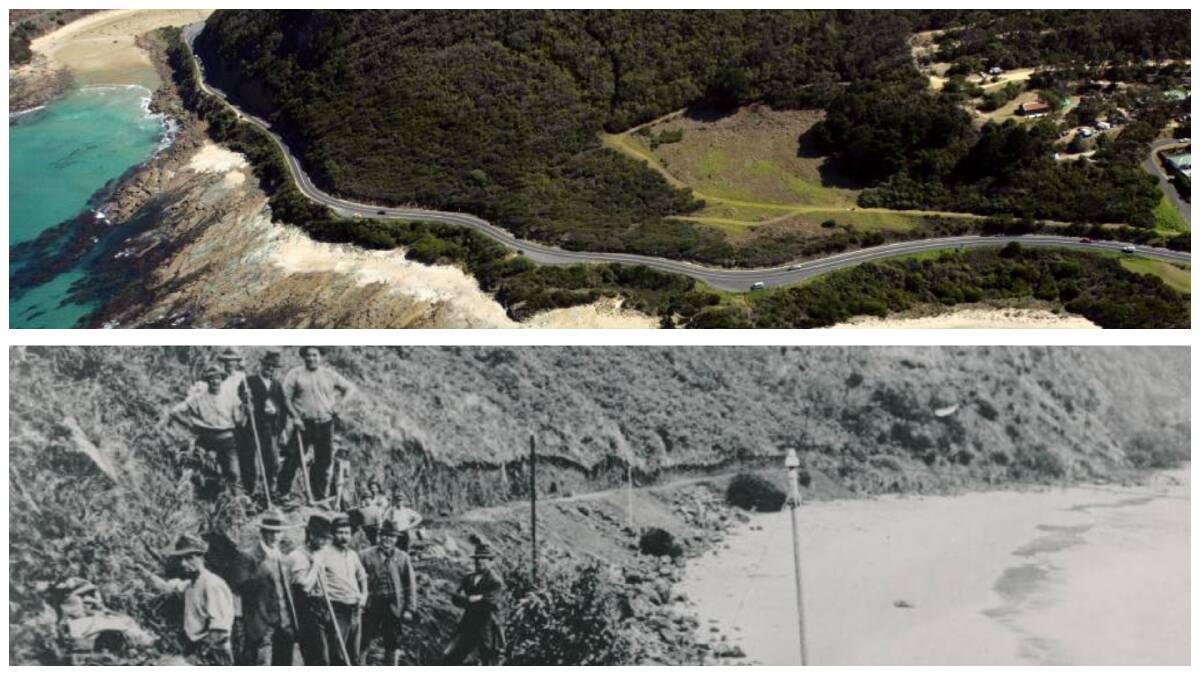

Snaking its way over 243 kilometres of dramatic, breathtaking coastline from Torquay to Allansford on Warrnambool’s doorstep, the Australian National Heritage-listed Great Ocean Road is iconic, a tourist magnet worth billions of dollars annually.

What most the six million annual visitors are unaware of is the road’s status as the world’s longest war memorial, carved by hand from the rugged coastal cliffs by damaged Diggers fresh from the trenches, in honour of their fallen mates.

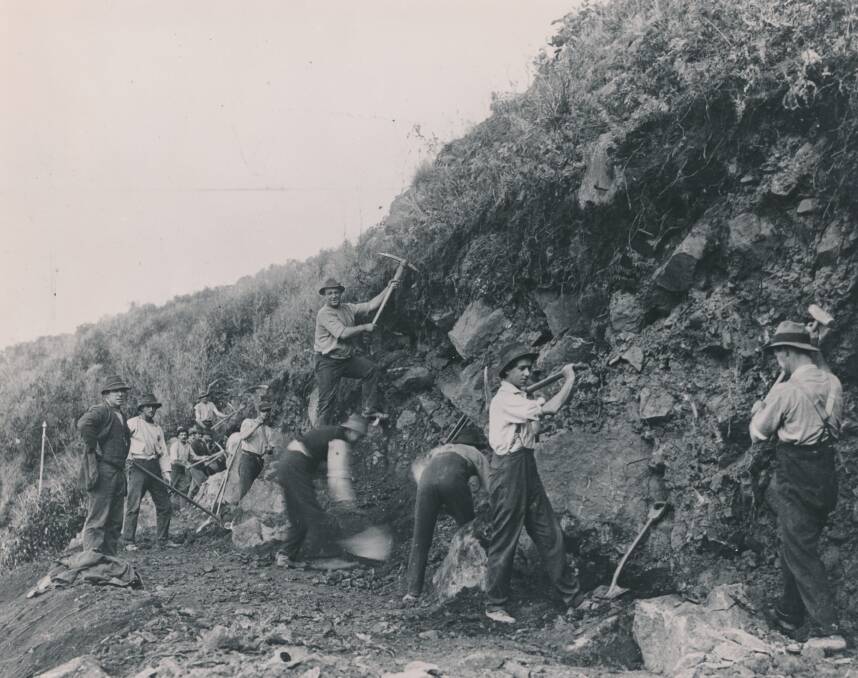

Dangling by ropes tied to their waists anchored to tree trunks on cliffsides above the pounding sea, they used picks and shovels instead of guns and bayonets, traumatised anew by the shudder of each gelignite blast through the cliff face.

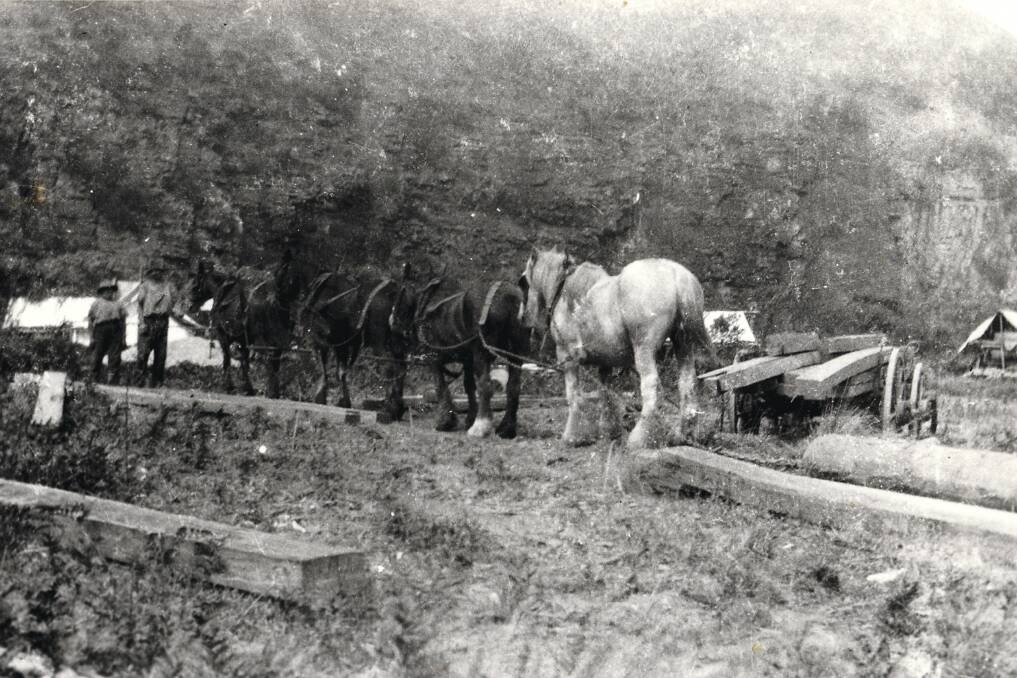

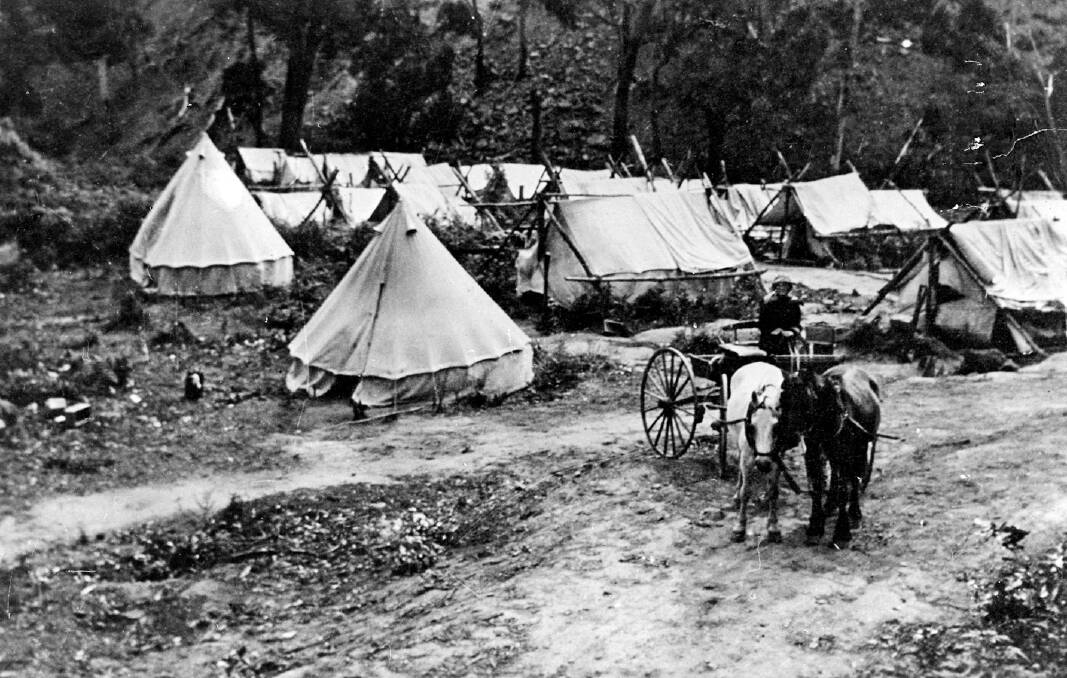

For their efforts, they were paid 10 shillings and sixpence a day and slept in old army tents.

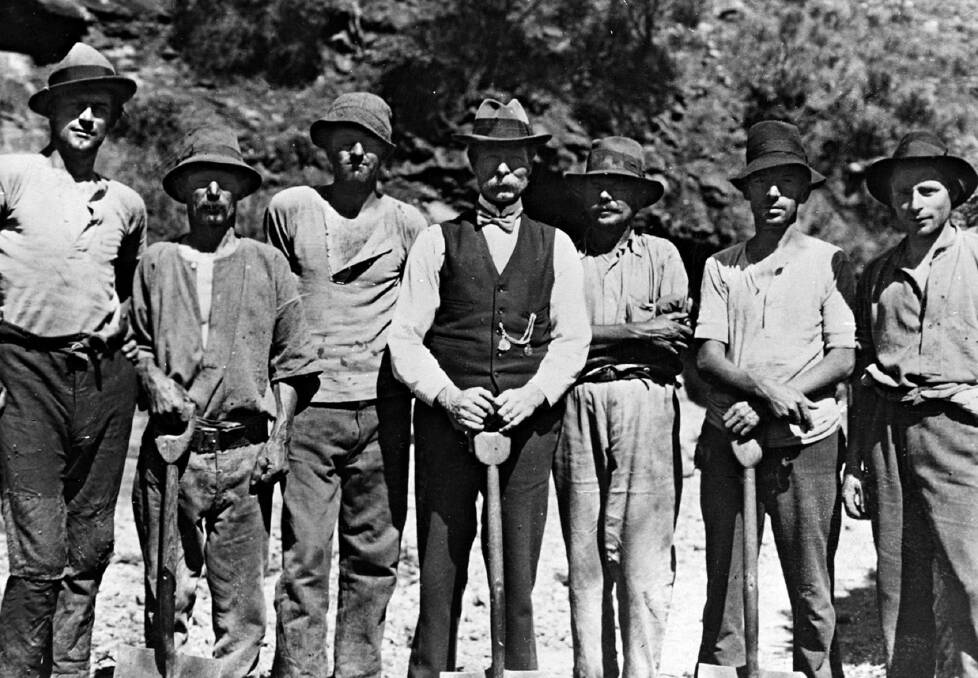

Some 3000 men – 2300 Great War soldiers and 700 work-for-the-dole participants – provided the labour for the project on the section from Eastern View through Lorne to Apollo Bay.

Designed primarily as a job creation scheme for ex-servicemen, the road was built between 1919 and 1932, opening up much-needed land access for coastal communities and creating a lasting memorial to the war dead.

The western portion of the road from Apollo Bay to Allansford was completed by the then Country Roads Board, although some sections remained unsealed until as late as the 1960s.

Sadly, the identities of the majority of those early road workers have been lost over time.

Just 390 have been identified, but in the lead-up to the centenary of the start of the road’s construction on September 19 next year, the push is on to name as many as possible.

Liz Price, general manager of Great Ocean Road Regional Tourism, says the centenary presents an important opportunity to acknowledge the early road workers.

“We need to be able to celebrate what is a momentous milestone and commemorate these people,” she said.

Ms Price has called on the families of road workers and engineers, long-time road residents and those with indigenous connections to come forward with their stories to help in the compilation of a centenary documentary, ‘The Story of the Road’ by production company Clothesline Content.

The documentary will be the centrepiece of the celebrations, featuring in a month-long event of screenings and pop-up cinemas housed in shipping containers across the region showing short films about each location.

In other centenary initiatives, beacon technology attached to park benches along the route will tell visitors the stories of the road.

Lorne Historical Society vice-president Peter Spring is part of a Great Ocean Road Regional Tourism reference group of tourist organisations and local councils formed to help stage the centenary events.

Mr Spring is hopeful of identifying more of the original road workers with the assistance of social media.

The database of 390 was compiled over the past decade by the historical society in collaboration with Portland Family History Group member, the late Iain Grant who conducted a national campaign to track down the road builders.

“It’s a different world of communications now and I’m optimistic we’ll get a good outcome,” Mr Spring said.

He is also hoping the history group will be successful in having its extensive collection of historic photos of the road’s construction available for public access in the online Victorian Collections.

The images provide a snapshot of tough physical work at times fraught with danger.

Before his death in 2010, Erwin Babington recalled soldiers cutting tracks through the bush to reach the clifftops in order to begin their drilling with manual jackhammers.

“Most times the men were tied to a tree with rope around them due to the steep terrain,” he recounted to his daughter Meryl Inderberg.

Mrs Inderberg said her father was just 10 years old in 1930 when he worked for a time with his father Ted who had the contract to supply timber for bridges and railings as the road progressed from Anglesea to Apollo Bay.

NOW and THEN: Grab the slide on the right of the image and slide it left

He had the distinction of being the youngest worker on the road.

“They would let the charge off to blow down the cliff face and then the hard work was to remove the falling rock and dirt. They also used a 16-pound hammer to break what did not require blowing,” he said at the time.

Mrs Inderberg, of Geelong, says driving the road which was such a large part of life for her father and grandfather makes her emotional to this day.

The family of sawmillers was also responsible for supplying timber for three successive arches built at Eastern View in 1939, ’63 and ’79.

After serving his country for a year on the Western Front, Private Cecil DeLay returned home to Waurn Ponds in 1917 looking for work.

He found it two years later on the Great Ocean Road project.

Cecil died in the early 1960s, but not before recounting his time on the road to his friend Jack Harriott.

“He bought two horse and drays and worked on the road carting rocks for sixpence a dray-load. He got an extra threepence a load if he spread it. He used to say, by gee, it was good money,” Mr Harriott recalls.

Known as the ‘father of the road’, former Geelong mayor Howard Hitchcock was the project’s key driver, voted chairman of the Great Ocean Road Trust after its formation at Colac Town Hall on March 22, 1918.

Its charter was to oversee the road and raise the estimated 150,000-pound price tag.

Funding came mainly from subscriptions and land sales, later supplemented by tolls.

Although Mr Hitchcock died just three months before the road’s official opening by the Governor Sir William Irvine on November 26, 1932, his car was driven behind the Governor’s in the official cavalcade as a tribute to his contribution.

At 96, lifelong Lorne resident, historian and author Doug Stirling was born in the early days of the road’s construction.

As a 10-year-old in 1932 he stood in the crowd in front of Lorne’s Grand Pacific Hotel, watching as Governor Irvine used a pair of gold scissors to cut the purple ribbon to open the Lorne to Apollo Bay section.

Until the first maintenance gangs came through in the following years, the road was “in a very rudimentary condition”, he recalls.

“There were great boulders sticking out on the sides of the road. It was pretty dicey, rough and narrow with passing points and designated times of travel. It was just a corrugated, vibrating experience until the road was sealed,” he said.

Much of the road was one-way and in 1922 a tollgate had been installed at Grassy Creek to help meet expenses. Motorists were charged 2/6 (25 cents) and passengers 1/- (10 cents).

Mr Stirling said the opening of the road transformed life for residents of coastal communities who were isolated when bad weather halted access from the sea by steamship, or overland by coach through the Otways.

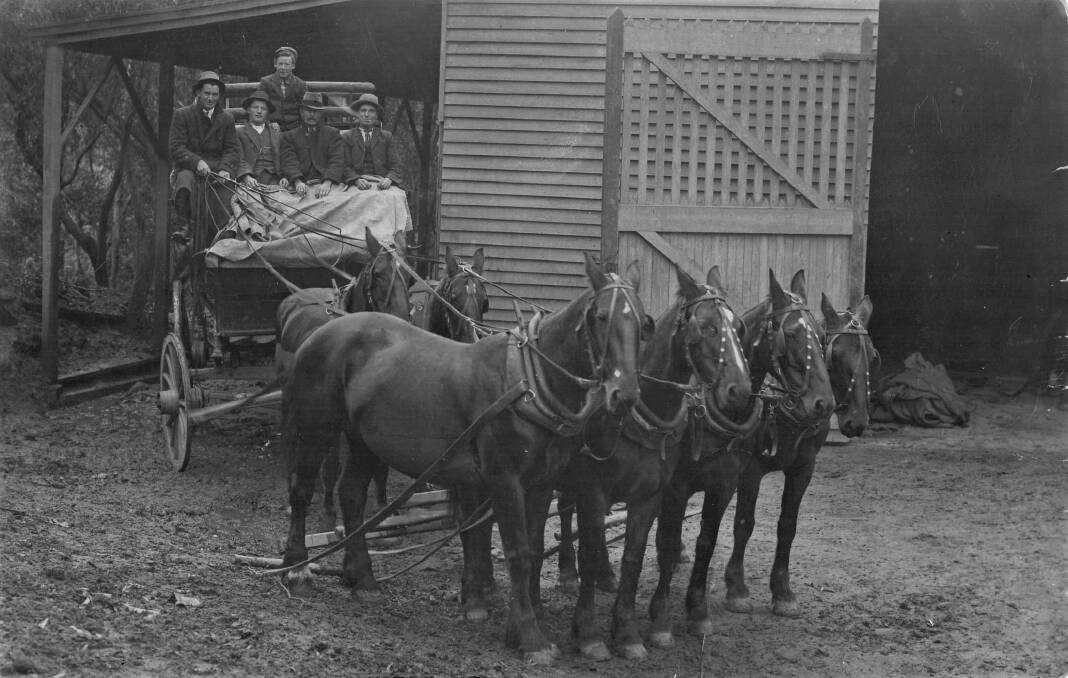

Bill Mountjoy’s forebears were among Lorne’s early pioneers, running a coach service in competition with Cobb and Co from Birregurra and later Dean’s Marsh to Lorne where they ran the Erskine House guest house.

Before enlisting as a vet in World War I, his father, Stan would often drive the coach the six-hour journey, ferrying up to 26 passengers through often boggy, steep tracks.

When the advent of the Great Ocean Road put paid to their coaching business, the Mountjoys turned their focus to their growing tourism enterprise.

The Standard acknowledges the assistance of the Lorne Historical Society in preparing this article. Anyone with information about the Great Ocean Road and its construction is asked to email hello@clotheslinecontent.com by February 28, 2019