The first time he was sexually abused Dominic Ridsdale remembers counting the tiny holes on the vinyl roof of his uncle's car.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

“I just wanted to remove myself from what was happening,” he said.

His uncle disgraced paedophile priest Gerald Ridsdale had taken him for a drive on the pretext of fixing the headlights on his car.

He was 12.

He remembers his uncle pulling the car over and getting out to check the headlights.

The shadow of Ridsdale was illuminated by the bright lights.

He could see his uncle, hands in pockets, staring at him through the windscreen.

It's an image that still haunts him.

"A person's hands are always large to look at for a child," Dominic said. "But on this night, I felt like his hands reached from my neck to my knees."

Dominic cried himself to sleep that night.

“I was so scared to tell anyone about it because I was so ashamed, I thought I would be punished.”

He developed a fear of his uncle so entrenched it stopped him disclosing his abuse until almost 30 years later.

"He told me if I told anyone, I would die," Dominic said. "I still feel that way now. I just clamp up. I can't talk about it because I feel like if I do, I'm going to die. I get angry because I couldn't get angry when I was a kid.”

The sexual abuse spanned years and occurred across Victoria, from his Ballarat family home, to holidays in White Cliffs, Edenhope and Apollo Bay.

"It didn't matter if my dad was staying there or there were other priests around," he said. "Nothing would stop him."

Ridsdale would sneak into his bedroom or corner him alone. If Dominic resisted he would beat him and threaten to kill him if he told anyone.

In 1993, Gerald Ridsdale was convicted of more than 100 charges of sexual abuse against children over about 30 years.

Dominic is the second relative abused by Ridsdale to publicly share his story.

His cousin David revealed his abuse in 1993. Dominic believed more of his cousins were abused and the full extent of the horror Ridsdale inflicted on children, including his own nieces and nephews, may never be known.

"The Royal Commission is just skirting the surface," Dominic said. "It's a big jigsaw puzzle of destruction and over the years we are getting pieces of that puzzle but I don't think all those pieces will ever come out."

Dominic battles depression, severe anxiety and has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. He is on antidepressants. He drinks every night to numb the pain.

“Every time I don’t drink I dream,” he said. “I have nightmares and flashbacks.. then I can’t sleep and I am up all night. That’s why I have my mandatory six beers a night.”

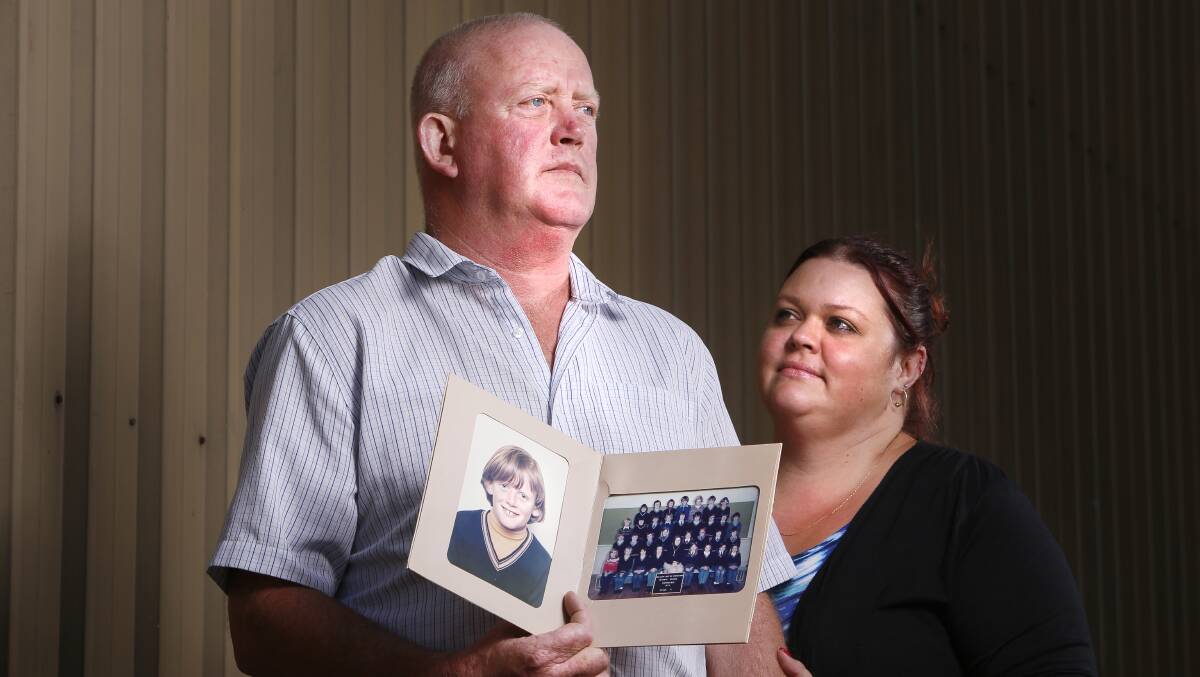

His fiancée Lana Johnston hears Dominic (who she refers to as Nick) crying out in the night.

“It’s heartbreaking because even when he sleeps, he can’t escape it,” she said.

Dominic’s emotions are always bubbling just beneath the surface. He has battled suicidal thoughts and made attempts to end his life. He has uncontrollable fits of rage that leave him exhausted.

He lives his life on alert, unsure of what may trigger a breakdown. He could be struck down by a flashback in the middle of country Victoria and become immobilised in his truck.

“I have to pull over on the side of the road because it all becomes too much,” he said.

“The tears come and I just freeze up.You have good days and you have sh..t days. You have days where you just don't want to get out of bed and talking to somebody is too hard.Everything just gets bottled up inside and then the next minute I’ll explode."

He said meeting Lana in 2007 changed his life.

“She hasn’t left my side,” he said. “I truly believe she saved me.”

Dominic came forward in the hope others suffering in silence have the courage to seek help.

“I’m doing this to support all the other fellas already fighting for the survivors,” he said.

“Even if it encourages just one person to come forward and seek help then it’s all worth it to me.”

Dominic said joining the Ballarat Centre Against Sexual Assault mens’ survivor group was tough.

“I felt so guilty because he was my uncle and I felt like I was to blame for all their abuse,” he said.

“I couldn’t stop him from abusing me and I couldn’t save any other kids from him and I feel like I should have. He hurt them...he hurt us all.”

But he believed CASA senior counsellor Andrea Lockhart was a profound part of the reason he was still alive today.

"Andrea brought me back from the brink," he said. "I made a pact that I have to see her once a month."

Lana said the toll on partners of survivors was immense.

“Even when Nick talks about it now, he still has this overwhelming fear he will die,” Lana said.

“This is the hold he (Ridsdale) had on not just Nick but all children he abused. As somebody who loves Nick, it is awful for me to watch. It has huge ripple effects. Our children suffer, Nick suffers and his entire extended family suffers alongside countless victims because of this.”

In his teenage years the abuse trauma caused him to quit football because he was afraid to shower in the changeroom with the other boys.

Born into a devout Catholic family, Dominic stopped going to church after his Ridsdale abused him.

On Sunday mornings he would get up early and hide in a wardrobe in his cousin’s bedroom down the street from his home.

He eventually dropped out of school and often wonders how his life would have turned out had his childhood innocence not been so abruptly broken.

Both his parents died when he was a teenager without ever knowing about his abuse.

With the next hearing of the Royal Commission into child sex abuse in the Ballarat diocese just days away, Dominic and Lana want just one thing: The truth.

“You just need one of them to say ‘yes we knew this was happening and lets work out how we can fix this and move forward’,” Dominic said. “If one admitted it, then the rest would fall down around him.”

More than that, the couple want support systems for survivors and to protect future generations of children.

“At the end of the day we just want funding for the ongoing medical and psychological support Nick needs,” Lana said. “We want to see ongoing individualised care for all survivors based on their needs.”

Dominic said he doesn’t want “blood money” from the church. He wants hope for the future.

“If I got a house or a car out of the church everytime I would look at it, I would think of the abuse,” he said.

“I don’t want that. What I want is to somehow put this behind me. I want my relationship to stay intact, my kids and Lana to be around me and for me to able to lead a happy life.”

Recently, Dominic and his daughter Maya tied colourful Loud Fence ribbons to the gates of Ballarat cemetery for his parents and all the victims who have died prematurely as a result of the abuse.

Supporters of abuse victims started the Loud Fence movement during last year’s Royal Commission into sexual abuse hearings.

The ribbons are tied outside institutions as an overt response to traumas long held silent and a symbol of solidarity with sexual abuse victims.

It has since gone viral with Loud Fences created all over the world including at the gates of the Vatican and in London, New York and Bali.

“Seeing those ribbons around Ballarat gives me so much hope for the future,” Dominic said.

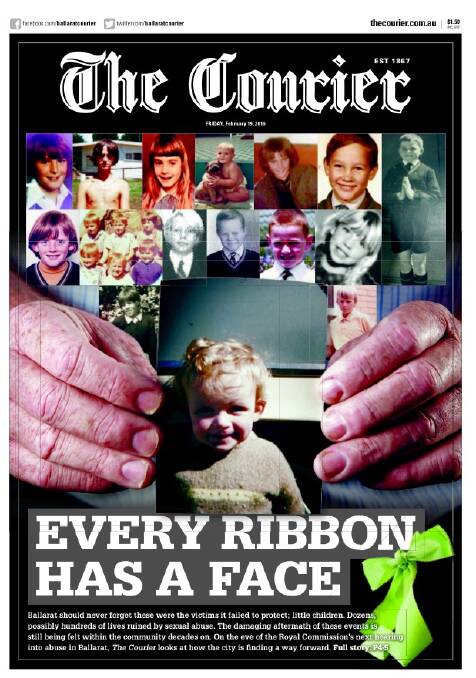

Faces of lost children bring hope for future

Every colourful ribbon tied to a Loud Fence in Ballarat has a face.

They are the faces of children whose innocence was broken by the very people meant to nurture and protect them.

Poignant photos of little children with the world at their feet. Images of children who have died prematurely because the abuse was too great to bear.

Images of children, who are now adults, facing a life sentence.

For the first time, a social media campaign is revealing the real faces of a systematic failure in the protection of children.

The Every Ribbon has a Face campaign is joint initiative between the city’s Loud Fence movement to end the silence on sexual abuse and the Ballarat So Sad Facebook page.

Dominic Ridsdale has shared his harrowing story of abuse at the hands of his paedophile uncle disgraced priest Gerald Ridsdale publicly for the first time.

He did so in the hope other victims suffering in silence across the city would find the courage to reach out.

SEE THE HARROWING GALLERY OF VICTIMS BELOW

Among the most tragic photos in the campaign are those with no human face like abuse survivor Gordon “Bushman Hilly” Hill whose image is a number.

He was an orphan at St Joseph’s Home at Sebastopol between 1943 to 1959. He suffered years physical, sexual and emotional abuse.

He was referred to as number 29.

Across the city a groundswell of support has wrapped itself around survivors in a bid to end years of denial by acknowledging their pain.

Their support is giving new hope to survivors leading a national charge which has attracted celebrity support and seen the rest of Australia follow.

Ballarat Centre Against Sexual Assault manager Shireen Gunn said community response campaigns were pivotal in ending the isolation felt by sex abuse victims.

“It acknowledges their abuse and creates a supportive environment they can heal,” she said. “Loud Fence has had a profound effect on survivors.”

It is such a widespread show of support that educates people because it starts conversations about sexual assault.”

The ripple effects of sexual abuse are inter-generational.

Ms Gunn said survivors were often triggered by their own children turning the same age as they were when they were abused.

“It impacts a victim’s ability to feel safe in parenting their children,”she said.

“Their experience was the world wasn’t safe for children.”

“Many of them feel a sense of that today.

“They could be emotionally detached or overly vigilant because they want to protect their own children from what they endured.”

One in three women and one in five men will be sexually abused in their lifetime.

“Many people are only starting to realise their relatives may have been sexually abused,” she said.

“The royal commission is bringing all of this to the surface and people are slowly putting pieces of the puzzle together.”

- Details: facebook.com/BallaratSoSad/ For help call CASA on 1800 806 292 or Lifeline on 13 11 14.

• To contact CASA, located on the corner of Vale and Edwards streets, Sebastopol, call 5320 3933 or free call 24 hours 1800 806 292.

Lifeline can be accessed on 13 11 14.