With farmers destroying milk rather than accepting below-cost processor offers, selling up and sending cows to slaughter or drying them off; with feed prices driven up by the drought and mental health counsellors being sought to assist those struggling; and with supermarkets engaged in a savage price war, it’s pertinent to ask: how did the Australian dairy industry get itself to this parlous position?

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

The past few weeks have seen the two major processors in the dairy industry in Australia, Fonterra and Murray-Goulburn, drastically revise downwards the prices they will pay for what are called milk solids. In an erratic move, this week they decided to raise those prices again, ostensibly in the face of an outcry from farmers and the wider community.

It all looks something like policy on the run – hardly something dairy farmers who, like all farmers, need to plan seasons ahead, can cope with. Yet the history of dairy in Australia is one of a great pendulum swing of over-regulation followed by complete deregulation.

In the 1920s, a plan to stabilise Australian butter and cheese prices was made, introducing a levy on local sales that was repaid to producers on exports, realising 3d to 4½d per pound of butter. Known as the Paterson plan, it was made compulsory by the Commonwealth Dairy Produce Act in 1934, which itself was found to be in breach of the Constitution in 1936, by regulating interstate trade. Nevertheless, the system continued on a voluntary basis.

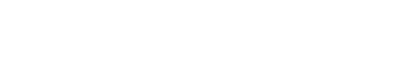

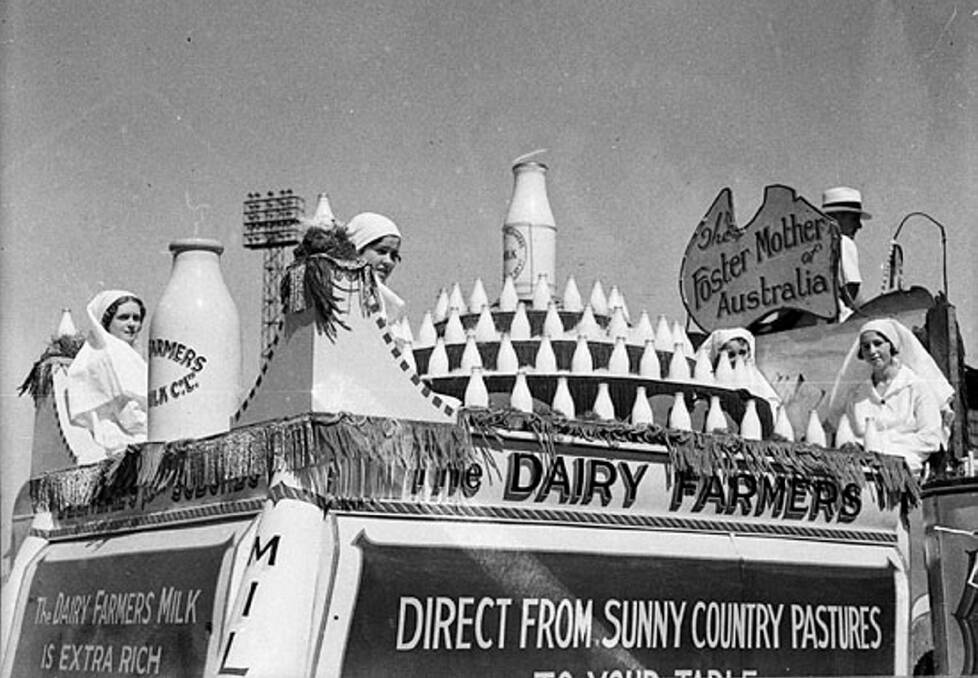

From 1935 until 1975, the Australian Dairy Produce Board regulated the sale and marketing of Australian dairy produce. A government body of considerable power and independence, it effectively named the prices farmers would receive through their state dairy boards and conducted negotiations for the sale of Australian dairy products such as butter and condensed and powdered milk – a market which boomed during the Second World War.

Prices paid to farmers were kept at artificially high levels through state acts of regulation and subsidies paid to negate inequities of trade, supported by the inherent strength of co-operative arrangements that maintained dairy infrastructure such as butter factories, and the fact that post-war reconstruction in Europe sucked up vast amounts of Australian primary produce at good prices.

In 1975 the ADPB was abolished and replaced by the Australian Dairy Corporation, which soon found itself mired in a corruption and tax evasion scandal involving one of its subsidiaries, Asia Dairy.

Despite its increasing dysfunction, including issuing credit cards to whomever it saw fit without reference to the Department of Primary Industries, the ADC continued to enjoy the support of successive ministers including Ian Sinclair and Peter Nixon. By the mid-1980s however the writing was on the wall. Hawke government primary industries minister John Kerin introduced the Dairy Produce Bill in May 1986, in the light of revelations that the dairy industry was receiving an average 57 per cent assistance, compared to 11 per cent for the rest of agriculture.

In a speech to Parliament in April of that year, John Kerin neatly summarised the agricultural dilemma: “World prices are the problem.” Tariff protection in the US and the European Economic Community was crushing Australian producers, but the government’s answer was to push on with reform.

The Kerin Plan, as it was known, caused outrage with its proposed abolition of the stabilisation and equalisation marketing that had existed previously, and the introduction of penalty levies for above quota production. Victoria as the largest dairy-producing state especially resisted the plan, and its stated aim of reducing the number of dairy farming holdings.

It was replaced in the 1990s by the Crean Plan, after Paul Keating directed the Industry Commission (now the Productivity Commission) to inquire into the dairy industry.

The Commission was scathing.

It found “that the (industry) interventions caused Australian consumers to pay around $280 million more for fresh milk and dairy products in 1989-90. This involves an annual loss to consumers and a corresponding gain to the dairy industry.” It proposed sweeping changes, noting that existing state regulations “appear to be used for poorly specified social objectives, as well as to provide assistance to the farming sector of the industry… the Commission recommends that State controls over the supply and pricing of fresh milk should be removed, and recognises the need to do so gradually to avoid undue disruption to the industry.”

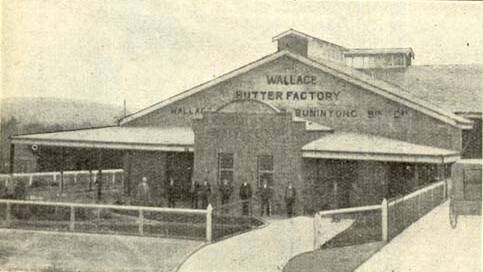

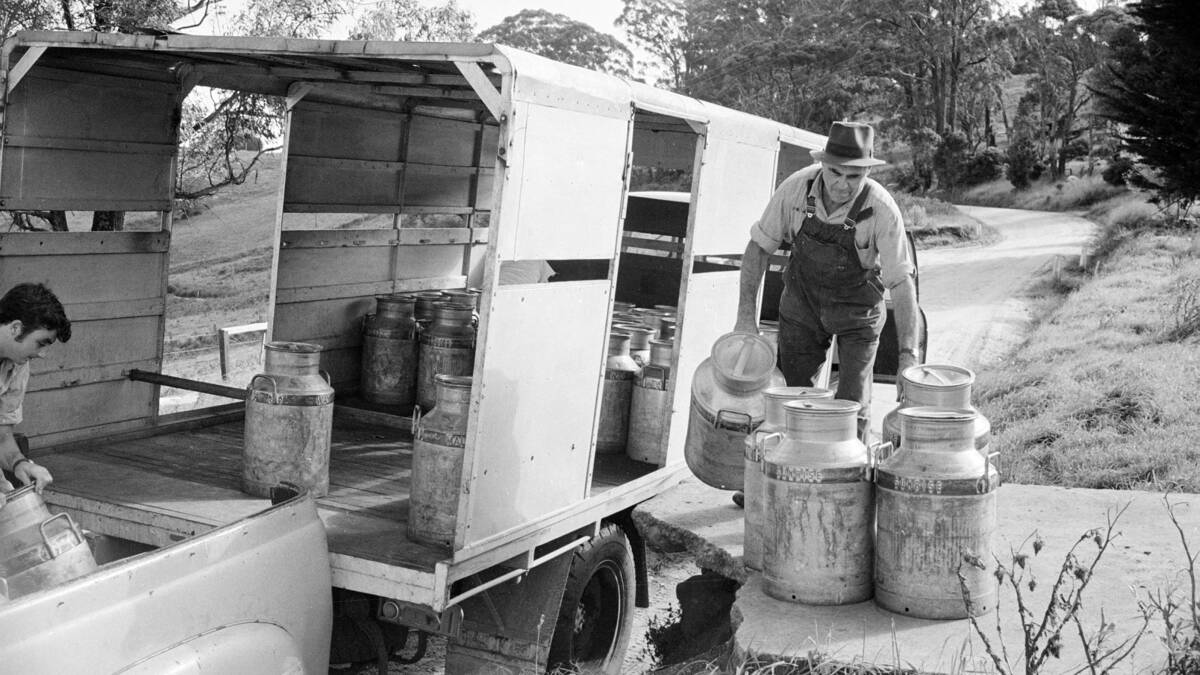

The end of the 1990s saw commercial consolidation, the removal of state production quotas, and a mass exodus of farmers from the industry. In the 1930s, almost 150,000 people were employed in the dairy industry. This fell to around 40,000 to 50,000 towards the 2000s, and the dairy herd fell from a national total of over 3 million dairy cows in the 1940s to 1.6 million cows by 2000.

On July 1st, 2000, the dairy industry was deregulated by Joe Hockey, then minister for financial services and regulation, following the lead of other primary industries in the country and the findings of the Hilmer Report, which discerned no public benefit to the two remaining price support mechanisms: market milk pricing, paying more for drinking milk than manufacturing milk; and domestic market support levies, feeding money back from sales to milk producers.

Outside of milk producers, the processors set themselves for a ferocious battle for control of the manufacturing milk resources in Australia. Prices would be set by the world market, and the big players –Murray-Goulburn, Bonlac, Fonterra, Parmalat – moved in. At the same time, the supermarkets realised that by cutting margins on milk, they could destroy small competition and pull consumers into their stores.

The free market had arrived, and dairy farmers are now feeling its caustic downside.