As mysteries go, it has the elements of a blockbuster.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

An authentic Australian war hero, larger than life, ebullient and tragic. A man decorated for his service not only by his own country, but by foreign governments as well. A man remembered in the main street of Ballarat with a bronze statue and by having his alma mater name a school house after him

Another Australian soldier, also highly decorated. A man with a past that included being a mercenary, a calculating thief and a cunning fraudster, but also a passionate historian and respected author. A immensely brave man with a reputation of public service in first aid that was not unquestioned.

And the unfortunate convergence of events that led to him being employed at the Australian War Memorial in a role that required a person of integrity and honesty: qualities he was endowed with, but not to the exclusion of his obsession with collecting – or stealing – valuable and historical militaria.

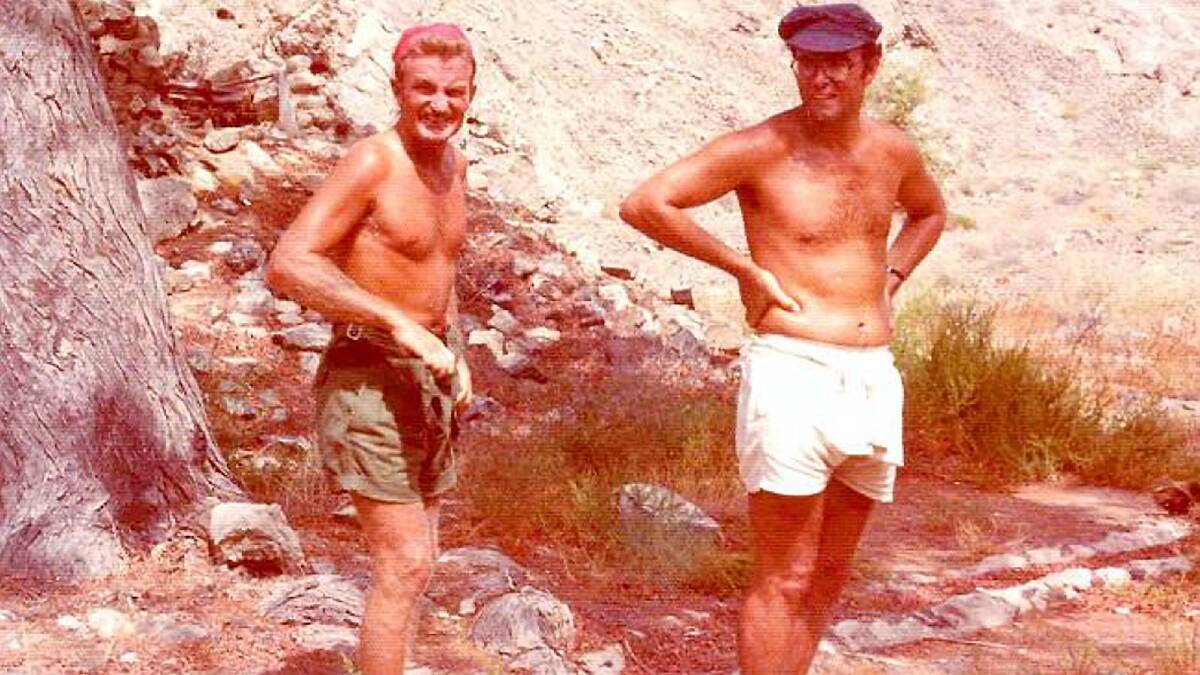

By the few accounts available of his existence, Rex Clark could have been a dashing Australian hero in the mould of Albert Jacka, Lesley ‘Bull’ Allen or Harold ‘Pompey’ Elliott. A member of the famous, fearsome Australian Army Training Team Vietnam (AATTV), he was part of a unit that was specially selected for their skills in fighting counter-insurgencies and jungle warfare. The AATTV were the most-decorated unit by far in Vietnam, and Rex Clark was one of the most decorated members of the team. Clark was a member of the AATTV for just 11 months, but served in Vietnam again in 1972. He also allegedly served with US forces secretly in Cambodia.

He won bravery medals from the US government for retrieving wounded soldiers from a minefield, and from the South Vietnamese regime for saving a drowning girl in Da Nang harbour. The list of foreign decorations he received numbers no less than 13 for his Vietnam service alone.

Still Major Rex Clark managed to get himself written out of history.

Details of his life are scant. He was born in 1935 in Inverell, NSW and joined the Australian Army in 1963. While on leave in 1975, he raised the ire of his employer by serving as a mercenary in Iran for the dictator Shah Reza Pahlavi. In his service Clark was awarded the Gold Star of Valour, apparently then the Persian equivalent of the Victoria Cross, again for rescuing wounded men. He fought for the Omani forces and was decorated by the Sultan Qaboos bin Said al-Said for bravery. He also fought as a mercenary in Rhodesia.

He was made an Officer Brother in the Order of St John for his services to the St John Ambulance Brigade in Canberra during the 1970s, yet in the history of the brigade it’s recorded that he was the instigator of a ‘military faction’ that had ‘pretensions to a rescue service’ and ‘engaged in intemperate correspondence’ with the St John headquarters. He was requested to resign, and complied.

But it is in his work as an expert in military history and the restoration of decorations and artefacts that Clark and Harold ‘Pompey’ Elliott cross paths.

Ballarat historian Dave Wright says Clark was working at the Australian War Memorial in the 1970s.

“He was one of the unofficial army historians connected with the museum, still connected with the army, and connected with several other museums over in England.”

After Pompey Elliott’s suicide in 1931 his medal group, including honours from Great Britain, France and Russia, passed from his family to the AWM. They subsequently disappeared.

“What might have happened is that Rex Clark, who was in the army and associated with the museum at the time, took the originals,” says Mr Wright.

“A lot of medals went missing, and a lot of medal groups – big medal groups, properly-named medal groups to high-ranking officers – were replaced by non-named medals.”

“They looked the same, so when they opened the drawers up there they were. So without thorough inspection – on Australian medals the recipient’s name is engraved on the rim – they’d do the stocktake, say, ‘yeah, it’s all there, not a problem…’

But the thefts were not limited to Australia.

“He did a lot of travelling for the army,” says Mr Wright, and military records show that Rex Clark was on army staff stationed in England at certain times from the 1960s onwards.

“It really hit the fan when a museum in England said, ‘we’ve got two Victoria Cross groups missing and the only person that’s been signed into this area is Major Rex Clark from the Australian Army. An investigation has started.’ The Australian War Memorial did their investigation; the Army history unit did their investigation.”

The full extent of their losses has never been revealed.

In 1974, The Age reported that an extradition had been sought for Major Clark to England on a charge of conspiracy to steal, stealing, receiving stolen goods and bribery. Though that case lapsed, the investigations were in train.

“The Military Police, the Federal Police, were called in, and as far as I know the investigation is still going on. There are medals missing everywhere,” says David Wright.

People across Australia reported sending family medals to Major Clark for free mounting, and having shiny new medals returned to them. They assumed they were polished. They were wrong.

As the degree of his fraud began to be revealed, the man with largest collection of Australian medals existing, and with an encyclopaedic knowledge of our war history, took to his room in Page in the ACT and shot himself. He was 43. Among the relics recovered after his death were the battle tunics of John Monash and Thomas Blamey.

They had been stolen from the Australian War Memorial. Harold ‘Pompey’ Elliott’s medals have never been found.

The Australian War Memorial declined to be interviewed for this article.