It was world-famous in its day: a meeting point for international actors and performers who later mingled with the Ballarat public in a renowned oyster bar run by the venue next door.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

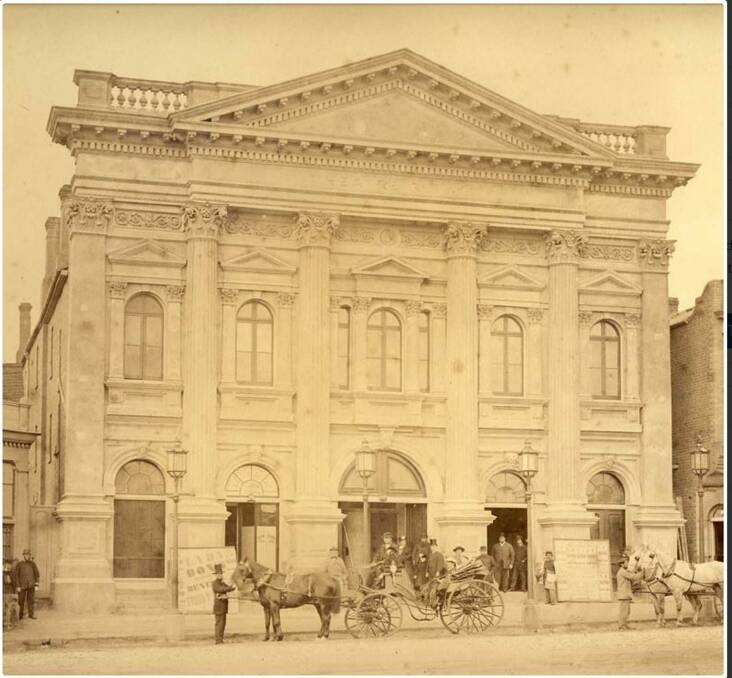

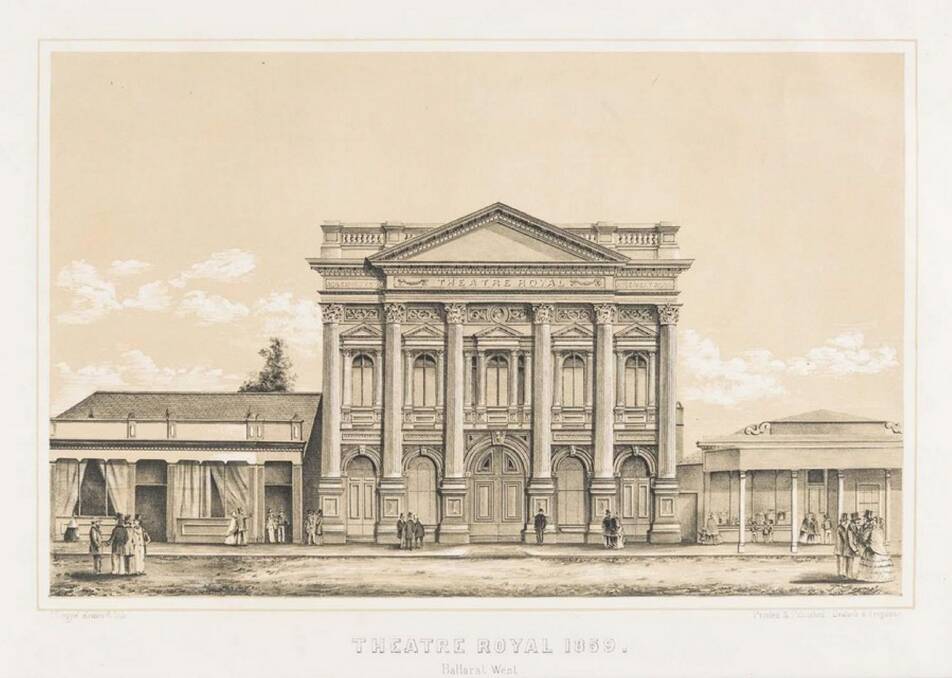

The Theatre Royal in Sturt Street was an imposing venue, the first permanent theatre built in inland Australia. With its massive Corinthian columns and Grecian frontage, five front entrances and main street presence, it sent a message to its competitors in Main Road, Ballarat East like the Montezuma and Charlie Napier theatres, and even the Ballaarat Mechanics' Institute, that it was the main player in the growing city.

Yet by 1880 its time as a performance theatre was done. It had lasted just over 22 years following its construction in 1858. Not long after, in 1899, a fire destroyed much of the fabric of this once-dominant presence in the city. Today there are traces of it left in the lanes and alleys and walls of the buildings there now, but the astonishing and renowned facade is a memory.

What happened to this grand theatre? As it happens, there's more to the story than just bad management or a change in public taste for entertainments, although those elements were a part of the story.

Rather a growing movement for temperance and the increased influence of Methodism in an ever-more conservative Ballarat saw a shift in the power structures of the city, a shift that led to a disapproval of 'low entertainments' and 'bawdy provocations'.

The Theatre Royal may have advertised itself as a venue for the latest theatrical melodramas and operatic attractions, but in reality it was not above putting on shows that were not so educative, such as minstrel programs, marionette performances and 'Marsh's Juvenile Comics', described as 'A Company composed of little Girls and Boys under 13 years of age'.

Historian and PhD student Ailsa Brackley du Bois has examined the rise and fall of the Theatre Royal, and see in it a lifetime played out in three short acts - the first between its founding in 1858 and the early 1860s; the second in a brief interlude following its closure around 1864 and attempts to convert it to a temperance hall (and cordial factory); and its third iteration, reborn as a theatre only to suffer the indignity of an orchestrated riot, with performers chased through the streets.

Ms du Bois places the eventual demise of the grand building within a larger narrative in Ballarat, one that saw the inhabitants of the city keen to erase the early memories of the 'wild days' of the Goldfields era with a more 'respectable' and sober outlook.

The original concept of 'theatres' on the goldfields were not the large buildings we think of today such as Her Majesty's or the Princess Theatre in Melbourne, but rather smaller venues attached to hotels. These rooms were designed purely to help relieve the male diggers of even more of their hard-earned income than the already over-priced and often adulterated liquor they were being served. The 'theatre' often consisted of dancing girls, magic shows and musical interludes, becoming increasingly lascivious as the drunken patrons clamoured for more.

Most of these were in the Ballarat East and Main Road areas of the city, located upon the diggings, and many were little more than timber and canvas lean-to arrangements, with some striving to respectabilty in timber and shingle.

It was world-famous in its day: a meeting point for international actors and performers who later mingled with the Ballarat public in a renowned oyster bar run by the venue next door. But the temperance movement became quite obsessed with the Theatre Royal.

- Ailsa Brackley du Bois

The Theatre Royal changed this. It was designed to make a statement and to draw touring acts of a higher standard, to set itself above the muddy throng and attract a clientele of a better class. For a time, it succeeded beyond the proprietor's wildest dreams, maintaining its own actors and musicians, supporting a stage crew and scenic artists, impossibly important for the tableaux so popular as an entertainment in the 1860s.

The actor-manger and impresario Charles Kean, son of the legendary and celebrated tragedian Edmund Kean, performed for ten nights at the Theatre Royal in February 1864 with his wife, the renowned actress Ellen Tree. According to records, 'their receipts (in Ballarat) were higher than elsewhere in the tour: miners gave gold nuggets to Mrs Kean and an old man walked over a hundred miles to see them.'

But trouble was brewing. The Ballaarat Mechanics' Institute had posed itself as a rival venue, and had the moral upper hand as a educational institution. At the same time, community pastimes such as choral groups, eisteddfods and even bell-ringing became more popular. The Theatre Royal was losing money.

It soon closed, and was sold to a cordial-making firm, who promptly sold it to The Ballarat Temperance League, planning to convert it to a hall for their anti-alcohol rallies. Sore must have been their surprise to discover a pre-existing contract with the hotelier next door, a Mr Bouchier, stipulating the building had to run as theatre. The league backed out of the deal. They cautioned respectable families to stay clear of the theatre which they now considered 'a lost cause'.

Despite a visit from the Prince of Wales in 1867 causing a sensation, by the 1870s the theatre was looping from Shakespearean successes to second-rate 'fakir' shows. In 1877 a disastrous and possibly orchestrated riot saw a mob assault the stage with “head-breaking” lemonade bottles, causing costly damage, then chase the frightened puppeteers of Levity's Original Royal Marionettes down Sturt Street.

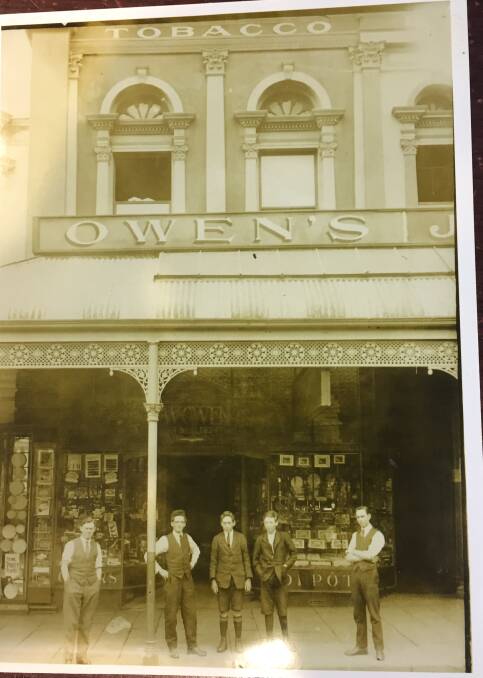

It was the final straw. Soon after the theatre closed, to become a drapery, then a series of different businesses. Today a spiral staircase at the rear of the contemporary buildings and a lonely bluestone pillar are all that remain of the mighty Theatre Royal.

Deepest thanks to Ailsa Brackley du Bois for her assistance and the use of her article Repairing the Disjointed Narrative of Ballarat's Theatre Royal, and to Terry Frangos of Kafeeneo and Dinah Toohey of Owen Williams for unfettered access to their premises.